Commodifying Consent, or Why the Consent Condom is a Dumb Idea

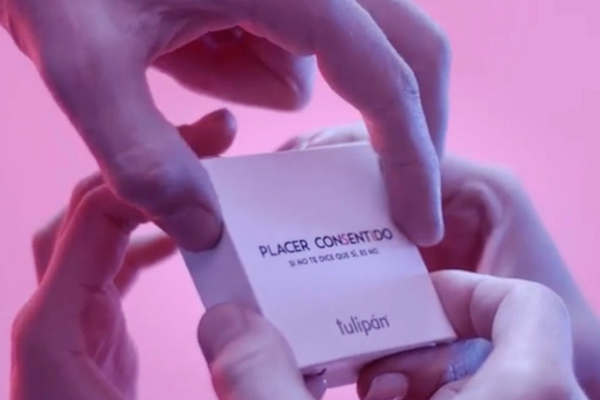

Earlier this month, an Argentinian company called Tulipán launched something of a viral marketing campaign for what the internet is calling a “consent condom.” You may rightfully ask, “How does that work?” The answer is, unfortunately, a little too simple. The condom’s packaging requires that four buttons on its box be depressed simultaneously—using four hands—in order for it to open, the design aiming to promote sex that two, two-handed partners have consented to. Here’s why it’s a really dumb idea.

You’ve heard it before, you’ll hear it again, but let’s just say it once more loud and clear for everyone who’s missed it: consent is a dialogue, and it needs to be perpetually renegotiated. At any given time during a sexual encounter, a partner could decide that they are no longer having fun, and revoke their consent. And the act of giving your consent can certainly not be reduced to one moment, or be contained in one single action, like in the pressing of a button. In order for an encounter to be truly consensual, an ongoing, nuanced discussion is required, and products like the “consent condom” get it wrong by reductively framing consent as a simple, sign-on-the-dotted-line type of contractual agreement.

Tulipán’s condom packaging calls to mind other misguided attempts at marketing consent, like the “consent apps” that popped up last year in the wake of #metoo, such as the disturbingly titled “LegalFling” or the eerily evidentiary and unsexy “ConsentAmour.” What these products inadvertently prioritize in their very design is the patriarchal and creepy need to record, to “solve” the "problem" of consent by producing evidence of a partner having, at one point, said yes. They market themselves as removing the grey-areas of consent by facilitating proof of a one-time consensus, but in doing so disregard that an essential aspect of consent is that it can be given, and then at a moment’s notice, taken away.

The message that lives in the “consent condom,” as in most products aimed at addressing consent, is one of liability more than anything resembling personal responsibility or shared equality. These products point to the lack of education surrounding consent, and to the fact that the nuances of sexual intimacy simply cannot be distilled into a contract-based tool, or mediating service. The major failing of products addressing consent is that they tend to understand it in market terms, that is, as transactional, traded from one hand to another in a single exchange, instead of as a continual conversation.

The most glaring problem with Tulipán’s product, like most every recent effort to commodify consent, is that it shows a very shallow interpretation of what consent actually is: an active discussion. As we’ve mentioned in other journal entries, no matter what you've said yes to before, you can always, always say no, and this is the key factor that products like Tulipán’s don’t seem to grasp. When it comes to safe sex, we love condoms, but when it comes to consent, we're not convinced the “consent condom” is making anyone feel safe.

Olivia Whittick is a writer based in Montreal. She is managing editor at Editorial Magazine, and an editor at SSENSE.